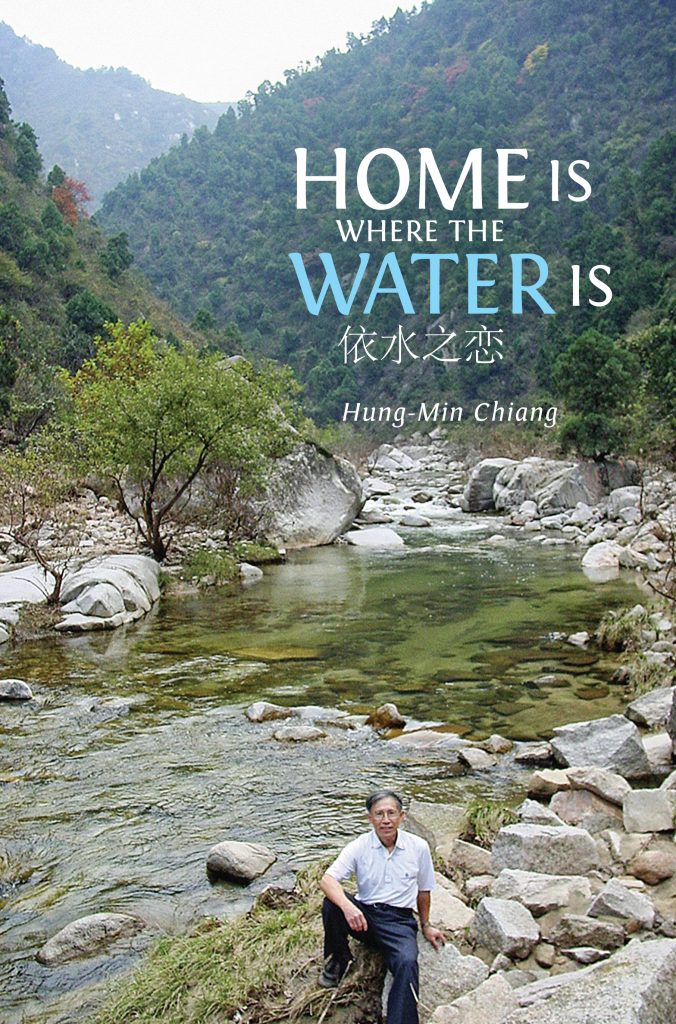

by Hung-Min Chiang

Born and raised in tumultuous times in East Asia, Hung-Min Chiang survived earthquakes, wars, foreign occupation, dictatorship, and illness before making his way to PEI. While navigating his perilous journey, Chiang learned and practiced “The Way of Water,” Daoist lessons for living drawn from Nature. Home Is Where the Water Is examines the many critical turning points in a life and how these shaped the person he became.

Throughout his memoir, Chiang reflects on the lessons of his mentor, American psychologist Abraham Maslow (1908–1970) and his ancestor Chiang Taigong (1128–1015 BC), a wacky old fisherman whose outlandish techniques caught the attention of a king. His fascination with these enigmatic figures led to a lifetime of questions and a rewarding career in psychology. Home Is Where the Water Is reveals how Dr. Chiang overcame adversity to find both his calling and happiness in North America with his wife Mei-chih and their three daughters.

April 2020

328 pages, softcover, 100 black and white photos, $27.95

ISBN 978-1-988692-33-3

Also available as a PDF

Listen to an interview with Min Chiang on CBC’s Mainstreet PEI.

Hung-Min Chiang received his PhD from Brandeis University, where he studied and worked with renowned psychologist Abraham H. Maslow. Together they co-edited The Healthy Personality: Readings. Dr. Chiang is also the award-winning author of Chinese Islanders: Making a Home in the New World. Dr. Chiang taught Psychology at the University of Prince Edward Island for many years. A humanist at heart, he is remembered fondly by his students as a dedicated, highly original, and inspiring professor with a self-deprecating sense of humour. He lives with his wife Mei-chih in a house overlooking the Charlottetown Harbour where three rivers meet.

Q & A with Min Chiang, author of Home Is Where the Water Is

Q: Is there a particular moment when you knew it was important to share your autobiography?

A: My original plan was to write a brief family history for my grandchildren. However, as the project progressed, the focus of my work gradually shifted to myself—how and why I have become who I am. This required a great deal of honest self-examination and self-disclosure.

By nature, I am a very private person and to disclose myself publicly was the last thing I would do when I was young. However, once I open up, I am very candid; I cannot lie and I am very poor at making up a story. During my teaching years, I discovered to my surprise that self-disclosure in public was not at all hard; all I needed was a receptive audience.

Q: Many of the events depicted in the book happened a while ago. How did you recreate those scenes in such vivid detail?

A: I was a shy, sensitive child, poor at self-expression but good at observing what was going on around me. My ability to retain and recall these childhood memories was further aided by numerous family photos and home movies our parents took when we were young. Many books and pictorials about our clan, family and my hometown are now available in the market and also helped me place my personal experiences in their proper physical and social context.

When it comes to reconstructing past events, I am a stickler for details and accuracy. For example, the diagram of my childhood home that appears on page 33 was a result of my visit in 2002. Even though I knew the layout of the whole house by heart, I was not satisfied; I wanted know its precise physical dimensions. Armed with a measuring tape, and with the help of a group of eager local kids, I took measurements of each room down to the accuracy of an inch.

In the book I presented the quake as my earliest memory, but in reality there was another memory that might have preceded it. It was a memory of my sister and I being placed in a pair of large bamboo baskets suspended from the ends of a pole balanced on the shoulders of a porter on way to our summer home. Apparently my sister was too young to walk a four kilometre mountain trail, and I, a bit older, got to hitch a ride. As the porter paced himself along the mountain path, the baskets swayed up and down rhythmically, and I distinctly remember seeing the blue sky above. It was a brief, fragmented impression, but it was etched in my mind: the blueness of that sky.

Q: The first two sections of the book chronicle your experiences of living through war and foreign occupation. You share anecdotes of hiding neighbours from a mob in the bathroom and of being interrogated for sketching a nondescript government building. You grew up in a very tumultuous environment. What helped you to weather those uncertain and difficult times?

A: I did not see myself particularly being brave or heroic, as many other people were in the same boat as I was, and we all learned to suck it up.

However, I was singularly determined to answer my life’s calling, then only faintly heard. I was willing to go where angels fear to tread. My father called it my youthful recklessness, but my propensity to ignore risks once my mind is made up is a trait I have exhibited time and again throughout my career. Nietzsche has put it very eloquently: “He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.”

Q: Ideas from Daoist philosophy reoccur frequently throughout the book. Can you talk about “The Water Way” and how this has affected your approach to life?

A: This is an open, receptive and accepting attitude as opposed to an aggressive, assertive approach to life. Laozi compares it to water that flows naturally and spontaneously regardless of a terrain, and thus benefits myriad of things. Maslow used a term “Taoistic (Daoistic) receptivity” to describe this gentle, open attitude. I always try to accept people and not judge them, which makes life much more enjoyable.

Q: Many people know you as a professor who taught humanistic psychology at Prince of Wales College and UPEI. You have written a chapter called “Teaching by Doing Nothing,” which might strike some as an unorthodox approach to the classroom. Can you elaborate on this idea?

A: Basically, it is a student-centered approach that puts normal educational practice on its head. In most classrooms, a professor takes an active role and students, the role of passive learners. In my seminar, I gave students near total freedom in choosing the direction of their learning. Stunned and confused at first, they eventually came around and began to take an active role in learning. When this turnaround finally took place, it was electrifying and beautiful to watch. What they learned was not abstract book knowledge but meaningful, active, personal knowledge. Students aptly described our weekly seminar as “three-hours of living experience.” In my classes, there were no yawns or sleepy heads.

Q: You are an avid gardener whose seaside garden was featured in Canadian Gardening magazine. In Charlottetown, you are famous for Professor Chiang’s garlic chives and for sharing fresh spinach from your greenhouse. What keeps you coming back to the garden, year after year?

A: Simply put, it is a joy of watching things grow. Gardening offers a basic lesson in living and if you practice patiently, you will be amply rewarded with the fruit of your labor.

As an exercise regimen, gardening is far more exciting and rewarding than getting on an exercise machine. The latter makes one feel like a mouse on a treadmill; the former allows you to commune with Nature.

Q: Lifelong friendships have been at the core of your life from your childhood “Group of Five” to families such as the Birdwhistells, the Ramussens, and the Lins. How have these relationships shaped who you are today?

A: Old friends are like old shoes. The footwear fits snugly and they are comfortable; they help us get around day in and day out on the rough terrain of life. I keep many of my shoes for 20, 30 years or longer until the bottom falls off. I keep my good old friends even longer—until death do us part.

Every one of my good friends is different, yet they all have enriched my life. Taken together they are as important as water is to my identity. Without water’s buoyancy and sustenance, I might become as miserable as a jellyfish out of its element, collapsing and drying up, out of shape.

Q: What books have been influential in your life and why?

A: Abraham Maslow’s Motivation & Personality, with its positive view of human nature. It led me to its author who became my mentor and radically changed my life and career.

Laozi’s Dao De Ching, for its marvelous brevity, humor and insightful observation of life. If I were allowed to take only one book to space or to a deserted island, I would take this one.

Q: In your acknowledgements, you thank your wife, Mei-chih for being your rock for the last six decades. What do you admire most about her?

A: Her unwavering devotion and steady support, and her unparalleled sense of love and duty to the family. All too often I was a loving but easy-going parent, as the episode in the chapter “A Cabin in the Woods” illustrates, where each of our three little girls packed nothing but a bag of underwear for a long road trip. Had Mei-chih been in charge, she would have never allowed such a silly negligence to take place.

Q: How does the title of your book, Home Is Where the Water Is, reflect your relationship with different water bodies over the course of your life?

A: Not only is water the essence of life, for me it also symbolizes inclusiveness, naturalness, fluidity, transparency and spontaneity—all the traits I covet in my personal life.

Flowing (as in a river) or moving water (as in the ocean) cleans itself by mixing with and absorbing oxygen from the air, while healthy, natural still water does the same by letting the impurity sink and settle to the bottom by the very act of remaining still—just as meditation and self-reflection does for a person.

Intellectualization aside, I have simply learned to love and enjoy water in its various forms, such as rivers, springs, waterfalls, ponds, lakes, oceans and even mist and clouds, as each one has its own beauty. Personally, I like a small mountain stream most of all. I love to sit, watch and listen to the endless music of flowing water.